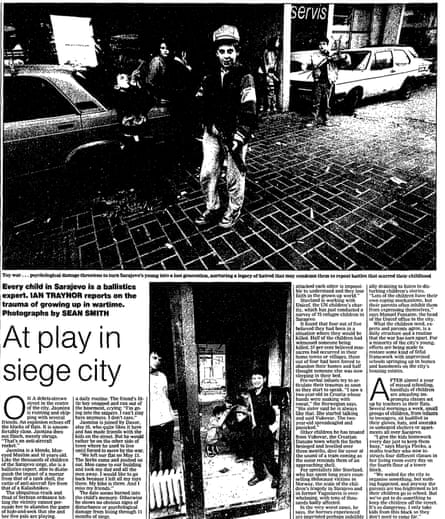

At play in siege city: every child in Sarajevo is a ballistics expert. Ian Traynor reports on the trauma of growing up in wartime

27 February 1993

On a debris-strewn street in the centre of the city, Jasmina is running and skipping with several friends. An explosion echoes off the blocks of flats. It is uncomfortably close. Jasmina does not flinch, merely shrugs. “That’s an anti-aircraft rocket.”

Jasmina is a blonde, blue-eyed Muslim and 10 years old. Like the thousands of children of the Sarajevo siege, she is a ballistics expert, able to distinguish the impact of a mortar from that of a tank shell, the rattle of anti-aircraft fire from that of a Kalashnikov.

The ubiquitous crack and thud of Serbian ordnance hitting the vicinity cannot persuade her to abandon the game of hide-and-seek that she and her five pals are playing.

“Sometimes we get a little frightened,” she says. “But we like playing better. My mum tells me not to go too far away.”

She shakes her pony tail, blows her bubble gum till it, too, explodes, and scrambles over a burnt-out car wreck whose roof has been turned into a rusty colander by dozens of bullet holes.

While Jasmina and her friends play on the street, Edin Serdarevic, an anxious father of two, loiters on the pavement keeping a discreet eye on them. “You can’t keep them cooped up in the flats the whole time,” he says.

After almost a year of terror and encirclement, the parents of Sarajevo have given up trying. Everywhere you go, urchins are on the streets, playing football and tennis in the housing estates amid heaps of burning rubbish, turning charred and gutted buildings into adventure playgrounds. If you sit midway up a tower block and listen to the din outside, the two dominant sounds are of children playing and bullets flying.

One woman tells of a friend in the frontline suburb of Grbavica where life in the shelters is a daily routine. The friend’s little boy snapped and ran out of the basement, crying: “I’m going into the snipers. I can’t stay here anymore. I don’t care.”

Jasmina is joined by Davor, also 10, who quite likes it here and has made friends with the kids on the street. But he would rather be on the other side of town where he used to live until forced to move by the war.

“We left our flat on May 13. The Serbs came and pushed us out. Men came to our building and took my dad and all the men away. I would like to go back because I left all my toys there. My bike is there. And I miss my friends.”

The date seems burned into the child’s memory. Otherwise he shows no obvious signs of disturbance or psychological damage from living through 11 months of siege.

But according to parents, paediatricians and child psychologists, the children of Sarajevo are being brutalised and traumatised by the siege, the terrible things that some of them have suffered or witnessed.

There are an estimated 62,000 children under the age of 14 in Sarajevo, about 20 per cent of the besieged population. According to the Bosnian government, 1,250 have been killed and 14,000 wounded over the past 11 months, arriving at the children’s department of the Kosevo hospital at an average rate of five to six every day.

“We had to amputate the leg of a three-month baby boy after he was hit by a sniper,” says Dr Salhudin Dizdarevic, the head of the children’s surgery department. “Usually the kids are hurt by shrapnel from the shelling. Maybe 40 per cent of them will remain incapacitated. We’ve had so many amputations, many of them are invalids and will not have a normal life. And many of them lost one or both of their parents at the same time. It’s a great tragedy.”

As the doctor runs through the chilling statistics of the war, Almira Lugic lies listlessly on her bed 70 days after being brought in.

She is 13 and looks about nine, mere skin and bone and large hollow eyes set in a sallow face. Her stomach, kidneys, liver and pancreas were severely damaged when a shell fell close to where she was waiting to fill a plastic bottle from a water pump near her home in an outlying Muslim suburb.

“We didn’t think she would survive,” says the doctor.

Her survival now seems assured, but apart from her physical injuries, she bears the mental scars from the other horrors she witnessed that day.

“I was standing beside a boy who was killed,” she says matter-of-factly. “I saw him being injured and dropping down. Then his head fell off.”

Almira’s experience is typical of the thousands of child victims of the Bosnian war and, according to experts, the psychological damage threatens to turn Sarajevo’s young into a lost generation, nurturing a legacy of hatred that may condemn them to repeat the battles that scarred their childhoods.

Serdarevic unwittingly echoes the views of the experts, saying his two children have become very aggressive. “They scream all the time and don’t speak properly any more. They have very bad dreams and often wake up screaming in the middle of the night. They dream that men with beards are coming into the city to get them. One of my friends has a big beard. The children knew him before, but now they are frightened of him.”

Rune Stuvland, a Norwegian child psychologist and one of the few experts working with the traumatised young of Bosnia and Croatia, says that the effect of a war that is incomprehensible to the unformed mind is to destroy children’s trust in adults. “Children basically trust people,” he says. “But the fact that neighbours became killers, friends became enemies, and families attacked each other is impossible to understand and they lose faith in the grown-up world.”

Stuvland is working with Unicef, the UN children’s charity, which has just conducted a survey of 75 refugee children in Sarajevo.

It found that four out of five believed they had been in a situation where they would be killed. Half of the children had witnessed someone being killed, 57 per cent believed massacres had occurred in their home towns or villages, three out of four had been forced to abandon their homes and half thought someone else was now sleeping in their bed.

Pre-verbal infants try to articulate their traumas as soon as they start to speak. “I saw a two-year-old in Croatia whose hands were soaking with sweat,” the Norwegian says. “His sister said he is always like that. She started talking and said Vukovar. The two-year-old spreadeagled and panicked.”

Other children he has treated from Vukovar, the Croatian Danube town which the Serbs besieged and levelled over three months, dive for cover at the sound of a tram coming as the noise reminds them of an approaching shell.

For specialists like Stuvland, who has spent long years counselling Holocaust victims in Norway, the scale of the children’s tragedy in Sarajevo and in former Yugoslavia is overwhelming, with tens of thousands badly affected.

In the very worst cases, he says, the horrors experienced are imprinted perhaps indelibly in the child’s brain. “What the child sees, hears, and smells is so strong that it is memorised in detail and the perception of it is stored. The picture, sounds, and smells can be re-experienced constantly. They are stored at the front of the brain and not processed. It can be like a constantly recurring horror movie.”

The difficulties of treatment are exacerbated by the fact that war trauma psychology is a young discipline, only receiving attention in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. In addition, successful treatment of scarred children is complicated by adult reluctance to confront the challenges.

“The important thing for the child is to communicate, to express themselves and recount what they have gone through,” says Stuvland.

All the experts agree that most children are happy to relate the horrors they have experienced and that, if reluctant, they should be coaxed.

But in Sarajevo, where the parents are demoralised and at their wits’ end waging a daily battle for survival, foraging for water, fuel, and food, it can often be too painful or emotionally draining to listen to disturbing children’s stories. “Lots of the children have their own coping mechanisms, but their parents often inhibit them from expressing themselves,” says Manuel Fontaine, the head of the Unicef office in the city.

What the children need, experts and parents agree, is a daily structure and a routine that the war has torn apart. For a minority of the city’s young, efforts are being made to restore some kind of fitful framework with improvised schools springing up in homes and basements on the city’s housing estates.

After almost a year of missed schooling, handfuls of children are attending impromptu classes set up by teachers in their flats. Several mornings a week, small groups of children, from infants to teenagers, sit huddled in their gloves, hats, and anoraks in unheated shelters or apartments all over Sarajevo.

“I give the kids homework every day just to keep them busy,” says Marija Plecko, a maths teacher who now instructs four different classes in her living room every day on the fourth floor of a tower block.

“We waited for the city to organise something, but nothing happened, and anyway the parents are too frightened to let their children go to school. But we’ve got to do something to keep the children off the street. It’s so dangerous. I only take kids from this block so they don’t need to come far.”

Mladen Jelicic, a well-known Sarajevo comic, also tries to occupy the city’s young by broadcasting four hours of school’s programmes on television each week. It’s a gesture, he says, but often useless. “Nobody can watch it, because usually there’s no electricity.” And despite the efforts of Plecko and her scores of colleagues, the vast majority of the city’s children are still going without any schooling at all.

They include Nusrat, a skinny, grinning little nine-year-old black with grime, who has spent several months in the Ljubica Ivezic orphanage in Sarajevo since his father was killed while fighting the Serbs. His mother was killed the same day by a mortar bomb. Nusrat has not been told and thinks his mother is in hospital in France – another case of trauma when the child is finally told.

“As far as children are concerned, the worst is still to come here,” says Manuel Fontaine of Unicef. “In terms of war trauma, we are now in the survival phase. Kids can be good at coping with that. But once the war is over, the worst phase is when they are trying to recover.”

Ian Traynor, Europe editor of the Guardian, died in 2016. Described as the ‘journalist’s journalist’, Ian covered post-cold war Europe, including the fall of the Berlin Wall and the expansion of the EU.

Maggie O’Kane was a Guardian foreign correspondent from 1992, covering the Yugoslav wars. In 1993 she was was named Journalist of the Year for her reporting from Bosnia.

Fighting talk: the first dead body of the war fell at a wedding. In the year that has passed thousands of Bosnians have been murdered and raped. And while the world huffs and puffs the Serbs pour scorn on Western threats and no-fly zones. Sarajevo continues to suffer

Maggie O’Kane

5 April 1993

There are five in the car riding high in the white hills above Sarajevo. The man in the middle of the back seat dangles a black German-made machinegun between his legs. He lifts it and pointing to the muzzle says: ‘I have taken 300 Muslims with this’. His identity card is a bright metallic blue with a white eagle’s crest. ‘Seselj,’ he says, ‘I run with Seselj’s men’. But today the man who fights with the most feared of the Serbian paramilitaries, Voyislav Seselj’s White Eagles, is on a day off.

It is the day the BBC World Service announces that Cyrus Vance is giving up peace talking to spend more time with his family the day the hard-line Bosnian Serb leader, Radovan Karadzic, took his self-proclaimed parliament to a town in the south of Bosnia and rubber-stamped the failure of the Owen-Vance peace plan the day the continuing of the war in Bosnia was as clear as a view of Sarajevo from the sights of the tanks on our hill.

It is a year since Bosnians voted by referendum to separate from the old Yugoslavia a year since the leadership of the Bosnian Serbs took fright and proclaimed their opposition to secession. A year since President Karadzic, in the seventh floor Olympic suite of the Holiday Inn, said: ‘It only takes a few dead bodies on the street to start the war. That is the Balkan tragedy’.

The first dead body of Bosnia’s war was a Serb shot at a wedding in the Bach Charchija suburb on March 2. The next night militant Serbs barricaded the streets, fighting broke out and the ‘few dead bodies’ that Dr Karadzic needed to make his war were on them. Slovenia and Croatia had wrestled themselves away from the Serbian-dominated former Yugoslavia – he would not allow Bosnia’s Serbs to go the same way.

The white eagle in the back of our car, with his black machinegun, had come to Sarajevo then to fight as the first of the heavy mortars landed on the streets, courtesy of the Yugoslav federal army and their patron, the Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic. And as Radovan Karadzic unrolled his map of Bosnia and outlined plans to separate the patchwork quilt of ethnic groups, naive journalists sat in his Olympic suite on the seventh floor and asked ‘how’? We had not heard of ‘ethnic cleansing’ then.

Pedja Cukevic, a Serb who lives now in the hills overlooking the city, was on those barricades on March 3 – ‘you might remember me on TV’, he says. ‘I had a black balaclava and I gave an interview to Sky News in French’. Good-looking Pedja is about as moderate as they come in this war. Behind the doors of his apartment he hangs a Kalashnikov over a flash blue-check jacket. Sallow, bulky, 25-year-old Pedja wears a tiny diamond stud in his left ear, learnt his French in Lucerne where he played professional football, sleeps on a Japanese futon and likes Pink Floyd – all the accessories of a good-time boy. Girlfriends move in and out of his flat and left their lipsticks in his bathroom cabinet, but he preferred to hang about with Eldin, the Muslim friend he never thought of as being a Muslim. For six months Eldin dossed in his flat – the six months before the first shots of the war were fired. He left for the west side of the river – Muslim Sarajevo – three months into the war.

The hotel receptionist remembers the night last April when Serbian paramilitaries surrounded her apartment block on the west bank of the river and called out the Serbian men. Her Serbian neighbours, she said, were forced to join them. ‘If you were a Serb you were with them or against them and they had the guns.’ The Bosnian Muslims hit back, searching the Serbian men on the streets, stopping them on their way to work, looking for guns in their homes. The division of the Bosnian people a la Karadzic had begun. The Serbs went to the hills and the siege began.

The winding mountain road above Pedja’s house overlooks Sarajevo. It is spring on the mountain and the snow is melting. In roughly built chunky log cabins the men bombing Sarajevo are making coffee and puffs of smoke rise from their metallic chimneys. The melting snow reveals walls built from the stacks of bottle green ammunition boxes. The road is dotted with tanks wrapped in tarpaulins the colour of roast coffee beans.

The landmarks of Sarajevo below are easy to make out. The yellow Holiday Inn where the foreign journalists live, where you can pick out the Reuters office on the fifth floor, the BBC window on the third. Its front is gashed by mortars: ‘Nothing higher than the fifth and something at the back if you have it’ is the usual request at hotel reception. Further along the street towards the centre of the town the blackened municipal tower block is still standing and as our car winds down the hill to the Serb military headquarters on the east bank, we ease to the edge of the road to let the tank they call Black George, twice the width of a London bus, pass. The river divides Sarajevo under siege on the west with Serbian Sarajevo on the east but today Black George is ambling – for there is a ceasefire.

In the Serb military command headquarters we listen to the lunchtime news over potato soup and chunks of bread and raspberry jam. Pedja and his friends are amused at the translation from the BBC World Service news hour programme. Particularly, General Colin Powell’s talk of sticks and carrot being used against the Serbs. The Serbs, he is telling a New York press conference, are under ‘growing pressure’ from the international community to sign the Owen-Vance peace plan and that the security council resolution to impose a no-fly zone is part of a new ‘tough stand’ adopted by the West. ‘So you’re going to shoot down our planes, then,’ says Pedja. ‘But we don’t need to fly planes to win. We don’t fly and you don’t shoot –simple.’ The Serbian policy of ‘ethnic cleansing’ which has displaced more than a million people in a war against civilians, is conducted by shelling and mortaring the towns and villages until the population flees and then sending in the hard-line hit squads to clear out what remains of the fighters. In the early months of the war, army helicopters were used to transport fighting units and arms into Bosnia. But the tanks have been in position now for a long time. By the end of last summer the grass had grown long around the caterpillar treads of the tanks on the hills over Gorazde and Sarajevo.

‘Who needs planes?’ It’s been a long year for Pedja and he has lost many friends. His footballer’s leg is peppered with shrapnel, and he believes all the propaganda pumped out by the Serbian press agency. He knows there are thousands of Serbs being tortured in Sarajevo, Serbian women are raped in camps inside Sarajevo – he’s not sure where – but he knows they are there. He also knows the Serbs are not finished that they have ‘more cleaning’ to do and when they are ready they will stop the war in Bosnia.

General Powell’s announcement that warplanes from Britain, France and Holland will be flying over Sarajevo within two weeks is greeted with a shrug. Pedja’s commander Milan says he is not worried either. ‘They wouldn’t dare get involved in a war with us. The Americans remember Vietnam. They won’t take the risk’.

Milan is an engineer who grew up and grew old in Sarajevo. He says he does not think of the buildings of his city he is shelling with the tanks on the hill. This is war. But sometimes he dreams of walking across the bridge to the university where he taught.

A huge khaki curtain hangs on a bend on this side of the mountain to shield the cars from the snipers in Sarajevo. Peep around the side of the curtain and you can catch a glimpse of the occasional car racing by 200 yards away on the other side. Pedja doesn’t think about who he is shooting at or where their tank shells are landing. His friends, like Eldin, are Muslims now on the other side and after a year of war he says it can never ‘be like it was before. It becomes automatic, you shoot at the enemy and you don’t think about it or think about what is happening to Sarajevo. I love that town but war is not a time for thinking’. He still talks to Eldin on the phone. ‘One day, after I’ve been to the front at Dobrinja I called him. I said, ‘We gave you a good run for it today, where were you?’ and he tells me Dobrinja and I think to myself ‘I’ve spent all day trying to kill Eldin’.

Pedja opens another packet of Marlboro cigarettes and pours a glass of red wine from Dubrovnik. Ask him about the West’s great hope that tougher sanctions against Serbia will force Slobodan Milosevic to turn the screws on the Bosnian Serbs to sign up for the Owen-Vance Plan and he says: ‘It doesn’t matter to us what Milosevic thinks. I go up to Belgrade to buy a shirt and get some cigarettes. That’s all we need from Belgrade. We’re only using 40 per cent of the arms we have’.

When the Bosnian Serbs needed arms at the beginning of the war, they were left with ample supplies when the old Yugoslav army pulled out of Bosnia. From beneath the table Pedja takes out his Kalashnikov. ‘When the Yugoslav army left some of them stayed behind to organise our weapons. I went down to the barracks outside Sarajevo, gave my name and they asked me what training I had and then gave me a Kalashnikov. When this war’s over I’ll have to give it back’.

On this side of the patchwork curtain hanging on a bend on the road, life is easy compared to the streets of Sarajevo. The supplies come along a Serbian-controlled corridor from Belgrade, their homes are heated with a piped gas supply and even the radiators in the post office are warm. Outside a woman called Liliana is reading Agatha Christie as she queues to call the friends and family she is at war with across the river. Cats lie in the sun with full bellies and Pedja and his friends have all the time in the world. ‘We don’t care what the West thinks of us. You journalists are trying to lose the war for us. So, we are the dogs of war and we will just get on with it’.

In Bosnia, the Serbs have slammed down the hatches to the outside world. Their deputy minister of information, Tudor Dutima, reflects the defiant paranoia of the Serbs. ‘All these threats about no-fly zones and intervention, you have understood nothing. Why don’t you come? It makes us happy. We don’t know how to live without pressure. For six centuries we have had nothing but the threat of war’.

They call the land they have taken in Bosnia the new Serbian Republic of Bosnia. It is run from the hillside town of Pale, just outside Sarajevo, and it is from here that they control the movements of journalists. On an average afternoon a smattering of the world’s press sit in the hotel Olympic, around tables covered in shabby white linen, taking it in turns to go upstairs to the third floor press bureau of the Serbian republic on a paper chase for accreditation. A paper from the authorities, a paper from the military, a paper from the civilian command . . . on such an average Thursday afternoon we paper chase until nightfall. CNN’s driver, a local Serb, is interrogated for three hours in the police headquarters. Reuters and World Television News wait for six hours for accreditation they are eventually refused. At the Serb-controlled checkpoints journalists are searched and robbed of their dollars and marks. The Sunday Times is strip-searched, Italian television’s armoured car stolen, the Austrians lose 40,000 marks and the car.

It seems a long time since the Serbs worried about being nice to the world’s media. The opinion of the world doesn’t matter any more and neither do we.

Conferences in New York and Geneva cut no ice here where there is still, in Pedja’s words ‘work to be done’. There’s still Srebrenica, the town of 40,000 people, where 13 women and children died last week, trampled to death in the fight for a place on the UN evacuation trucks. They also want Gorazde – with telescopic lenses the Serbian sniper’s rifles are so close they can pick out curtains fluttering on the Muslims’ windows.

At a road junction in the heart of Bosnia UN soldiers in blue berets stand shooting the breeze with a pretty Serbian translator while 16 trucks of aid for Srebrenica line the road. Stalled convoys, starving people – they are used to it. Britain’s ambassador to the UN, David Hannay, warns that the Security Council is ready to move ‘pretty quick’. Move pretty quick? Where? And do what? The skies over Bosnia may soon be flown by the best of British, French and Dutch planes keeping our Western consciences clear imposing a no-fly zone on Serbs who don’t need to fly.

Sardjan Srzo, a Serbian parliamentarian rejecting the Vance-Owen Peace Plan, set the tone at the weekend for his fellow parliamentarians: ‘Now we have snubbed the Western pressure. I can go back to my fighters with my head held high’.

Soon the self-styled dogs of war will take Srebrenica, where 40,000 starving men, women and children are trapped while the best of British, French and Dutch will fly high in a clear Bosnian sky.